To be listed on the CAMPOSOL TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

History of Murcia , Part 5

History of Murcia, From the 16th to 18th century

The History of Murcia Capital is written in 6 parts. To access the other sections, click below:

Part 1, Prehistoric Murcia, Click Prehistoric Murcia

Part 2, Of Romans and Visigoths, Click Romans and Visigoths

Part 3,Moors and Mursiya, Click Mursiya is born

Part 4,Mediaeval Murcia, Click Mediaeval Murcia

Part 5,From 16th to 18th Century, Click Murcia 16th to 18th Century

Part 6, From the end of the 18th Century to the beginning of the 21st, 18th to 21st Centuries

Charles V, Ruler of the Holy Roman Empire inherits the throne

Following the death of Isabel I ( 1451 to 1504), the Castilian monarchy entered a period of political instability, with various regencies and, in real terms, a power vacuum, until the accession to the throne of Carlos I in 1516, also known as Charles V, Ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, a man with a vast dominion, which included much of Central, Western and Southern Europe, and Spanish colonies in North, Central and South America, the Caribbean and Asia.

Following the death of Isabel I ( 1451 to 1504), the Castilian monarchy entered a period of political instability, with various regencies and, in real terms, a power vacuum, until the accession to the throne of Carlos I in 1516, also known as Charles V, Ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, a man with a vast dominion, which included much of Central, Western and Southern Europe, and Spanish colonies in North, Central and South America, the Caribbean and Asia.

The peace and prosperity which had been the keynotes of the reign of the Catholic monarchs was now continued under the House of Austria, and the figure of the “Corregidor”, a local representative of royal jurisdiction appointed directly by the monarch, assumed more importance in cities belonging to the Crown rather than the church, as was the case of Murcia.

The early 16th century was marked by an increase in population and a rise in the area’s economy, to a large degree due to the development of the silk industry in the Huerta, the murcian irrigated lands which surround the city. During the previous century there had been an extraordinary growth in the number of white mulberry trees, which are one of the silkworm’s ideal habitats, and both mulberries and silk now became staples of the Murcian economy.

Even today the streets of Murcia are lined by the mulberry trees, and the city’s primary school children are taught to nurture their own silkworms as a project in the spring term: in this way the traditions of the Huerta are still remembered. The silk worm links are also visually displayed in the Museo de la Ciudad, and there are some fascinating photographs showing the silk worm industry in the Centro de Visitantes de la Luz.

Even today the streets of Murcia are lined by the mulberry trees, and the city’s primary school children are taught to nurture their own silkworms as a project in the spring term: in this way the traditions of the Huerta are still remembered. The silk worm links are also visually displayed in the Museo de la Ciudad, and there are some fascinating photographs showing the silk worm industry in the Centro de Visitantes de la Luz.

The Campo de Murcia also developed economically and in terms of the population, with agricultural techniques advancing and thus being able to support a greater number of people.

In these times of growth, the main aim of the ruling classes was to maintain and increase their wealth through their land and estates. But the increase in agricultural activity in the 16th century was not sufficient to solve the problems which arose when a growing population was faced with regular failures in the cereal crop, and this led to the beginnings of a new crisis.

The Revolt of the Comuneros

When Carlos I came to the throne in 1516 new social tensions arose. The King was frequently absent from the country, due to the vast extent of his kingdom, and both the aristocracy and the local governments in the larger cities were frustrated by the appointment of foreigners to administrative posts in the various kingdoms of the peninsula. This led to the outbreak of the Revolt of the Comuneros in 1519, and the revolt of the Brotherhoods in Aragón.

When Carlos I came to the throne in 1516 new social tensions arose. The King was frequently absent from the country, due to the vast extent of his kingdom, and both the aristocracy and the local governments in the larger cities were frustrated by the appointment of foreigners to administrative posts in the various kingdoms of the peninsula. This led to the outbreak of the Revolt of the Comuneros in 1519, and the revolt of the Brotherhoods in Aragón.

In Murcia the Comunero movement was led by Pedro Fajardo, the First Marqués de los Vélez, whose interest lay mainly in consolidating his own authority over the area. When the movement ultimately failed in 1522, he was expelled from the kingdom.

At this time the Murcian population was clearly against the monarchy under Carlos I, but they later supported Felipe II in the suppression of the Moorish rebellion in Granada, earning the city the title of “Most Noble and Loyal”.

The 16th century ended with the succession to the throne of Felipe III, who was to finally drive out the Moors

Floods and plagues

At the start of the 17th century, there were small mosques dotted around the Huerta of Murcia, around which the communities lived from the silk industry. These communities consisted of Christians who lived side by side with the Moors who remained, following the reconquista. Many of the Moorish occupants had been driven out following the rebellions five centuries before, but those remaining had ben farming families, living peacefully in the countryside.

At the start of the 17th century, there were small mosques dotted around the Huerta of Murcia, around which the communities lived from the silk industry. These communities consisted of Christians who lived side by side with the Moors who remained, following the reconquista. Many of the Moorish occupants had been driven out following the rebellions five centuries before, but those remaining had ben farming families, living peacefully in the countryside.

This was the case in outlying areas such as La Ñora, Guadalupe, Espinardo, Aljucer, El Palmar, Algezares, Javalí Nuevo, La Alberca and Torreagüera. When the Moors were driven out this had an important effect on the Huerta, of course, but less so than in other areas of the Region, where the Moorish population was in the majority.

The expulsion began in Murcia in 1613, with former Moorish possessions passing to the Crown. Logically, a demographic imbalance was created, the areas depopulated yet again, and this was exacerbated by various epidemics and natural disasters. In 1648 the area of Murcia was dealt a terrible blow by an outbreak of the plague, and there were also long periods of drought, frequent autumn floods and even significant earthquakes.

The expulsion began in Murcia in 1613, with former Moorish possessions passing to the Crown. Logically, a demographic imbalance was created, the areas depopulated yet again, and this was exacerbated by various epidemics and natural disasters. In 1648 the area of Murcia was dealt a terrible blow by an outbreak of the plague, and there were also long periods of drought, frequent autumn floods and even significant earthquakes.

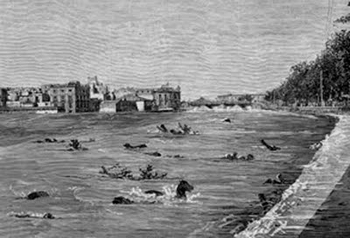

Perhaps the most serious event was the famous “San Calixto Flood” in 1651, which left more than a thousand dead and destroyed part of the poorer quarter of the city, as well as laying to waste most of the mulberry trees in the Huerta. The level of the floodwater reached the pulpit in the cathedral.( Images riada de Santa Teresa , another later flood)

All of these changes brought about a shift in the focus of subsequent activity in the Huerta, with attention now being turned to crops such as corn.

Growth of the silk trade.

The 18th century in Murcia was a period of splendor in many ways, based on a sharp rise in trade, especially related to the silk industry. Epidemics no longer ravaged the population so violently, and the population and its wealth both increased.

The 18th century in Murcia was a period of splendor in many ways, based on a sharp rise in trade, especially related to the silk industry. Epidemics no longer ravaged the population so violently, and the population and its wealth both increased.

Particularly notable was the increase in the number of people living in the cities, with the consequent rise in demand for basic products and a growing workforce available for employment in manufacturing activities. This generated a snowball effect, with the population of the capital demanding more and more agricultural production from the Huerta, and the first suburbs of the city grew, mainly housing day workers and craftsmen. At the same time, of course, the rich grew richer, as the landowners reaped the benefits of there being greater demand by increasing production and raising prices. Those to profit most were the clergy and the nobility.

In cultural and political terms, the century was marked by the Age of Enlightenment, which meant a more rational and dynamic society, ready to contemplate and accept new ideas. There was a new generation of individuals who were determined to end the isolation of Spain and the Spaniards and to move them forward into the greater scheme of modern Europe.

Neither the clergy nor the laymen were always keen to accept enlightened ideas, though, and the end of the century is characterized by their struggle against the cultural change and reformist ideas which were implied by Enlightenment culture.

The War of Succession, and Don Luis Belluga y Moncada

There are three key figures in the history of Murcia in the 18th century: Cardinal Belluga, the sculptor Francisco Salzillo ( Click Francisco Salzillo) and the politician Floridablanca.

There are three key figures in the history of Murcia in the 18th century: Cardinal Belluga, the sculptor Francisco Salzillo ( Click Francisco Salzillo) and the politician Floridablanca.

The new century began with a change of monarchic dynasty. Carlos II died without an heir to the throne, and Felipe V became the first member of the House of Borbón to occupy the throne of Spain. This transition was not achieved easily, though, with the War of Succession lasting from 1701 until 1714. This took on all the characteristics of a full-blown Civil War, with Catalunya and Aragón supporting the House of Austria, whilst Murcia threw its weight behind the Borbón cause.

Don Luis Belluga y Moncada, a priest, but also a military man by force of circumstance, as well as the driving force behind a large amount of charity and social work, played an important part in the political life of Spain, supporting Felipe V against the claims to the throne of Archduke Charles of Austria. He published a “Memorial” defending the rights of Felipe, and was appointed President of the Council of War of the Kingdom of Valencia, from where he coordinated armies.

In Murcia he fought off the enemy, who bombarded the city with their artillery, in the Battle of Huerto de las Bombas in 1706. ( Click battle Huerto de las Bombas. )During the previous 12 months the forces of the House of Austria had taken Cartagena, Alicante and Orihuela, and were closing in on Murcia, awaiting their opportunity. On 4th September, 1706, near where the Avenida Miguel de Cervantes now lies in the north of the city, some 400 supporters of Felipe occupied a large country house there and fought to prevent the Austria supporters from entering the city. Obeying an order from Belluga, they opened the sluice gates on all the irrigation channels and ditches in that part of the Huerta, flooding it and making it impossible for the opposing cavalry to manoeuvre effectively, and leaving the way clear for the invaders to be repelled. The place was still part of the Huerta until only about 25 years ago, and one of the streets is still called “Carril del Huerto de las Bombas”. It is now occupied by apartment buildings, but there is also a public park full of mulberry trees.

In Murcia he fought off the enemy, who bombarded the city with their artillery, in the Battle of Huerto de las Bombas in 1706. ( Click battle Huerto de las Bombas. )During the previous 12 months the forces of the House of Austria had taken Cartagena, Alicante and Orihuela, and were closing in on Murcia, awaiting their opportunity. On 4th September, 1706, near where the Avenida Miguel de Cervantes now lies in the north of the city, some 400 supporters of Felipe occupied a large country house there and fought to prevent the Austria supporters from entering the city. Obeying an order from Belluga, they opened the sluice gates on all the irrigation channels and ditches in that part of the Huerta, flooding it and making it impossible for the opposing cavalry to manoeuvre effectively, and leaving the way clear for the invaders to be repelled. The place was still part of the Huerta until only about 25 years ago, and one of the streets is still called “Carril del Huerto de las Bombas”. It is now occupied by apartment buildings, but there is also a public park full of mulberry trees.

The Battle of Huerto de las Bombas played a large part in the ultimate victory of the Borbón forces in the Region of Murcia and their final triumph at the Battle of Almansa.

As a reward for their loyalty and sacrifices during the war, Felipe V gave the Murcians the seventh crown on their coat of arms, as well as a lion with a fleur de lis on the centre, and around it the words “Priscas novisima exaltat et amor”.

The Count of Floridablanca

The Borbón victory in the War of Succession was also a triumph for the nobility of Murcia who had supported the cause of Felipe V. When peace arrived, relationships between the political classes of Murcia and the royal court were close throughout the rest of the century, and many members of Felipe’s government and subsequent administrations were drawn from the ranks of Murcia’s leading lights. One example of this was the career of José Moñino y Redondo, Count of Floridablanca, who was first Secretary of State between 1777 and 1792.

The Borbón victory in the War of Succession was also a triumph for the nobility of Murcia who had supported the cause of Felipe V. When peace arrived, relationships between the political classes of Murcia and the royal court were close throughout the rest of the century, and many members of Felipe’s government and subsequent administrations were drawn from the ranks of Murcia’s leading lights. One example of this was the career of José Moñino y Redondo, Count of Floridablanca, who was first Secretary of State between 1777 and 1792.

From his position at the centre of national government, the Count of Floridablanca was able to favour the city of Murcia on various occasions. He installed new factories and production techniques, allowed free trade, and instigated important water works in the shape of reservoirs and water supply, including the Reguerón which allowed the Guadalentín to flow into the Segura, thus reducing the violence of the sporadic floods which affect the city. He also developed new arable land, gave approval to the statutes of the Economic Society of Friends of the Country (which reflected the need for reforms in Murcia) and supported the culture of Enlightenment.

At a national level, Floridablanca divided the map of the country into 38 provinces, some of them (like Murcia) “kingdom-provinces”. Some of the towns which belonged to the area of the city of Murcia were Beniel, Abanilla, Santomera, Alcantarilla and Fortuna, as well as a whole host of villages from La Alberca to San Javier, and from Archena to Alhama.