To be listed on the CAMPOSOL TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

A history of Cartagena, part 4: from the 16th century to the present day

The millennia-old city of Cartagena becomes one of the most important naval bases in Spain

At the start of the 16th century in Spain there was, for the first time since the Reconquista began almost 300 years previously, a sense of national identity and unity, and the city of Cartagena, which had just returned to being a direct Crown dependency after 60 years of military governorships, approached this new era with every prospect of continuing to develop as one of the most important cities in Spain.

This followed a history of human settlement which is now thought to have begun over a million years ago (see the first in this series of articles about the history of Cartagena), the successive occupations during ancient history which ensured that the city would enjoy a heritage handed down from the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians as well as the Romans, and a troubled period after the Reconquista of Murcia from the Moors in the 13th century.

Cartagena under the House of Austria

Under the dynasty of the House of Austria, who ruled in Spain from 1516 to 1700, Cartagena continued to be a very important city, with a number of maritime operations both mercantile and military based here.

During the reign of Felipe III (1598-1621) the military strength of Spain declined, and Berber pirates constantly threatened coastal settlements and even those further inland. One of the most notorious of these pirates was known as "Morato Arráez", a name which crops up frequently, for example in relation to the Mazarrón Miracle and the history of San Javier. Eventually, Felipe realized that this situation could not continue, and decreed in retaliation that the remaining Moors should be expelled from Spain. To this end the royal Armada entered the port of Cartagena under the captaincy of Luis Fajardo, in order to transport all of the Moors of Murcia to Africa after they had been rounded up.

During the reign of Felipe III (1598-1621) the military strength of Spain declined, and Berber pirates constantly threatened coastal settlements and even those further inland. One of the most notorious of these pirates was known as "Morato Arráez", a name which crops up frequently, for example in relation to the Mazarrón Miracle and the history of San Javier. Eventually, Felipe realized that this situation could not continue, and decreed in retaliation that the remaining Moors should be expelled from Spain. To this end the royal Armada entered the port of Cartagena under the captaincy of Luis Fajardo, in order to transport all of the Moors of Murcia to Africa after they had been rounded up.

In the meantime, though, the local authorities in Cartagena were looking for ways to stimulate the city’s development, and proposed a series of measures. The proposals included the re-establishment of the Diocesan seat in the city, (following its transfer to Murcia in 1291), the diversion of the water from the Castril and Guardal rivers to the Campo de Cartagena, the creation of a chancery in Cartagena and the installation of a galley base in the port.

However, only the last of these ideas became a reality, in 1668, reflecting the fact that often a city’s development has to be “natural” rather than being designed by individuals with grand ideas. The spectacular growth of Cartagena as a trading port, and the diversion towards Italy of trade which had previously been carried out with Flanders and England, put the port firmly on map as a stopping-off point on the main trading routes.

But wars, economic problems in Italy and higher tax combined to send Cartagena into crisis in around 1620, and worse was to come when the population was decimated by the plague in 1648: signs of real recovery were not apparent until the end of the century.

Cartagena, Capital of the Maritime Department of the Mediterranean

After the death of Carlos II the War of Succession broke out, lasting from 1700 to 1713, pitting the claims of Felipe V

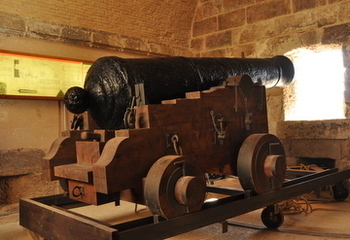

For Cartagena, the victory of Felipe V resulted in the city becoming a military bastion and a magnificent base for the new Imperial Navy. In carrying out this renovation the Bourbon monarchy restructured the peninsula into three maritime departments based in Cádiz, Ferrol and Cartagena, and after Cartagena became the capital of the Marine Department of the Mediterranean in 1726 construction of the Arsenal began four years later.

In the census of the Marqués de la Ensenada in 1755, Cartagena had a total of 28,467 inhabitants, without including the battalions and regiments of the military stationed here. Gradually, all the military buildings proposed by the “Ensenada Plan” were built, and in the second half of the century the new Casa del Rey and the Cuartel de Batallones were finished, while work continued on the Arsenal.

The Hospital Militar de la Marina, which has now been refurbished and is part of the Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, was finished in 1762.

In addition, work was finished on the Muralla de Carlos III, a fundamental part of the defences of the Arsenal and the Plaza de Cartagena, and various sections of the wall are still visible between the gates of the Docks and San José and the defences of the Arsenal.

In the 18th century, boosted by all of these important institutional and defensive structures, Cartagena as we know it today began to take shape and the population grew, both in the city centre and in the surrounding countryside.

Cartagena in the 19th century

After the optimism and growth of Cartagena in the 18th century, the city was plunged into crisis in the first part of the 19th. There were epidemics of malaria, tuberculosis, cholera and yellow fever, aggravated by the geographical characteristics of the area, especially the Almarjal swamp. Between 1798 and 1841 there was an extremely high mortality rate due to illness, and at the end of the 19th century it was decided that the Almarjal should be reclaimed as dry land in order to eradicate the epidemics.

Thus, in 1897 the great "Expansion, Reform and Sanitation" Plan known as the Ensanche was designed and launched by two engineers, Ramos Bascuñana and García Faria, and the architect Francisco de Oliver.

The Fall of the Old Régime

But while on one level Cartagena struggled to overcome the shortcomings of what from a military point of view was a strategically advantageous location, on other fronts the 19th century was one of rapid change.

In the same year, General Ignacio López Pinto described Cartagena as follows: "...this place was one of the most important points on the Peninsula, and one which the Government attended to with just good cause. A magnificent and well used port, the main trading point in the east of Spain; a Department of the Navy and Artillery; a large deposit of the equipment of war; the jetties from which our ships sailed for Africa; home to a large number of Spanish and Swiss troops and two Arsenals for the Navy and the Artillery, which between them employ 8,000 men ... Cartagena gave the impression of a large, lively city, where everything was alive with wealth and civilization".

Later in the century the city remained largely unaffected by the Carlist Wars, which were fought between the armies supporting the future Carlos V and the Royalists, who supported Queen Regent María Cristina and her infant daughter Isabel II. During these conflicts more important buildings were finished, such as the Plaza de Toros, built on top of the remains of the Roman Amphitheatre, and the Casino. In 1855 Cartagena received the title of "Excelencia" in reward for having been the first city in Spain to wage war with the French in 1808.

Cartagena was already strongly fortified, but it is from this time that fortifications of the port and the bay date, reputedly making it the strongest on the Mediterranean coast of Spain.

Furthermore, infrastructures and communications were improved when the lighthouse at Cabo de Paloswas built and the Cartagena-Albacete  railway line was opened, but in 1844 the calm was abruptly shattered when the National Militia and the people rose up to support the regency of General Espartero. This marked the start of a series of manifestations of unrest in Cartagena, continuing in 1868 when the Revolution triumphed in 1868, Isabel II left Spain, and a provisional government was installed for six years.

railway line was opened, but in 1844 the calm was abruptly shattered when the National Militia and the people rose up to support the regency of General Espartero. This marked the start of a series of manifestations of unrest in Cartagena, continuing in 1868 when the Revolution triumphed in 1868, Isabel II left Spain, and a provisional government was installed for six years.

When Amadeo I was made King in 1870 he arrived in Spain at Cartagena on board the frigate "Numancia", but this did nothing to quell federalist feelings in the city.

The Cantonal Rebellion

Amadeo I abdicated in 1873 and on 7th June a Federal Republic was proclaimed.

This lasted for eleven months, a period which was marked by confusion and political instability for a number of reasons, not least the Cantonal Rebellion. After the First Republic had been proclaimed, the people of Cartagena and other cities felt cheated when they saw that the government was in fact unitary rather than federal, while general discontent was also caused by the enlisting of young people for colonial wars like that of Cuba in 1868.

In this context Cartagena proclaimed itself a Canton on 12th July, 1873, and formed a revolutionary council in the Town Hall.

The main leader of the cantonal movement was Antonete Gálvez, a progressive military man of humble background, and in theory the Canton of Cartagena was in a strong position thanks to its military installations, including the Arsenal and the control the city had over a large part of Spain’s military navy. So far did the Canton advance that it even began to mint its own currency.

But despite other cities in Spain making similar gestures, the punishment dished out by the central authorities was severe, consisting of terrible bombardments throughout the six months of the Canton’s existence. Cartagena was the last independent canton to capitulate, surrendering on 12th January, 1874, although after Alfonso XII became king there was still to be another attempt at Republicanism in 1886 with the uprising of the Castillo de San Julián: this ended in the death of the city’s governor, Luis Fajardo, as he approached to negotiate with the rebels.

The Apogee of Mining and Modernism in Cartagena

After the failure of the Cantonal Rebellion, an exhausted and  devastated Cartagena faced the daunting task of regeneration. In 1860 various workers had left the city for the Sierra Minera to seek find their fortune, and this led to the creation of a separate Town Hall in La Unión, with the territory sub-divided into the areas of Garbanzal, Herrerías, Portmán and Roche.

devastated Cartagena faced the daunting task of regeneration. In 1860 various workers had left the city for the Sierra Minera to seek find their fortune, and this led to the creation of a separate Town Hall in La Unión, with the territory sub-divided into the areas of Garbanzal, Herrerías, Portmán and Roche.

Now, though, the people of Cartagena looked again to the mines to fund their recovery: plans were made for the reorganization and expansion of the city, and much work was undertaken on both infrastructures and more cosmetic changes. A new and ambitious approach to town planning was adopted: this was known as the Ensanche, and it included knocking down the defensive walls to build a new city with wide avenues and green areas.

The mines gave rise to a new commercial social class, who built their palatial residences in Cartagena. These include the homes of Senator Justo Aznar in Calle Jabonerías, of the Aguirre family in the Plaza de la Merced, of Pascual Riquelme opposite the Town Hall, the Pedreños family between Calle del Carmen and Jabonerías, the Huerto de las Bolas de Llagostera in Los Dolores, and a long list of sumptuous palaces and houses which gave the city its characteristic Modernist atmosphere. Foremost among the architects whose designs can be seen here is Víctor Beltrí, who perhaps more than any other is responsible for the turn-of-the century “nouveau riche” class in Cartagena leaving their mark on the modern city.

The demolition of the city walls was approved in 1902, but was never completed.

The twentieth century in Cartagena

But the wealth provided by the Sierra Minera proved not to be inexhaustible, and the decline which had set in by 1908 was hastened by the First World  War and the consequent reduction in mineral exports. Mines closed, factories were abandoned, and the city was in crisis again, as while the rich intended to continue to live in luxury the lower classes suffered the consequences of their failing businesses.

War and the consequent reduction in mineral exports. Mines closed, factories were abandoned, and the city was in crisis again, as while the rich intended to continue to live in luxury the lower classes suffered the consequences of their failing businesses.

In the 1920s there were signs of recovery. The Plaza de España was built, as was the Paseo de Alfonso XIII, and the final stage of the reclamation of the Almarjal was begun. Other important buildings were the Capitanía, the Plaza de San Francisco, the Plaza de la Merced, Plaza de Jaime Bosch, and the monument to the Heroes of Cavite and Santiago de Cuba was erected. Plans were drawn up and approved to bring drinking water from the river and reservoir of Taibilla, there was plenty of work in the docks, and the city became dynamic again.

In 1928 Isaac Peral’s historic submarine was tugged from Cádiz to Cartagena and made into a monument on the Esplanade of the submarine base. In 1965 it was donated to the city by the navy, and placed on another monument on the main seafront, and it was not until the start of the 21st century that the Peral submarine reached its present home in the Museo Naval.

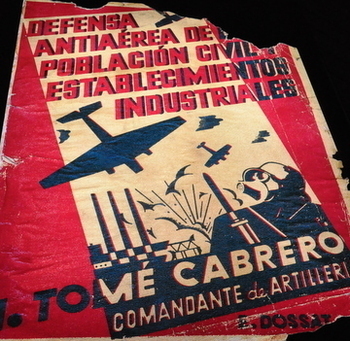

As one of Spain’s main naval bases the city of Cartagena inevitably played an important role during the

It was towards the end of the war that the tragic sinking of the Castillo de Ólite took place in the harbour, with the needless loss of 1,476 lives.

Reconstruction work after the war included, at last, the filling in of the Almarjal marshland, which was finally made completely dry with a view to future expansion. But malnutrition and contamination contributed to various epidemics and in October 1942, the city was flooded when the Benipila flood channel broke its banks during a “gota fría” episode of torrential rain.

The 1950s saw an increase in industrial, agricultural and naval activity, especially with the start-up of the petrochemical complex at Escombreras. This brought an immigrant workforce, along with factory and technical elements, which in turn contributed to the improvement of living standards and expansion in the Almarjal area. New areas of the city grew, such as Los Mateos, Lo Campano, Media Legua and Vista Alegre, and a constant water supply was guaranteed through the distribution of water from the Taibilla. Tourism also contributed, with the first development on La Manga del Mar Menor following the National Tourist Interest Law of 1963, which allowed tourist resorts to be built.

All of this brought about demographic stability, urban growth and better use of resources.

Democracy and the Present Day

In 1982 the Statute of the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia was passed, and since then, as well as being home to the regional parliament building, the city has fought to keep its history alive and to preserve and advertise its rich past, much of which is still visible in the old city centre.

At the same time, Cartagena has continued to build an industrial base while promoting its historical heritage with a view to tourism, and the port continues to play a key role in the development of the city as efforts are made to attract cruise ship visitors to the south-east of Spain. Indeed, with a coastline which runs from Cabo de Palos in the east to the bay of Mazarrón in the west, Cartagena is also popular among residential tourists, and the figure of over 2,000 British residents is the second highest among the 45 municipalities of the Region of Murcia (behind Mazarrón).

with a view to tourism, and the port continues to play a key role in the development of the city as efforts are made to attract cruise ship visitors to the south-east of Spain. Indeed, with a coastline which runs from Cabo de Palos in the east to the bay of Mazarrón in the west, Cartagena is also popular among residential tourists, and the figure of over 2,000 British residents is the second highest among the 45 municipalities of the Region of Murcia (behind Mazarrón).

But such is the strength of identity of the city of Cartagena, forged over millennia by an assortment of Mediterranean, African and European cultures, that many natives still feel the need to assert their independence from the “rival” city of Murcia, and this resulted in the latest manifestation of rebellion in 2015 with the election of a Mayor representing a local party rather than one of the mainstream national political groups. There can be little doubt that this feeling of being “different” is rooted in the historical developments which have been traced in the course of these articles, and which make Cartagena the unique city it is today. Following the reign of Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Áragon, the throne of Spain was finally unified into one country, the throne inherited by their daughter and in turn her son, Charles I who went on to become the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, King of Spain, Italy, The romans and Archduke of Austria, founding the House of Habsburg, also known as the House of Austria.